he sun is shining in the small riverside town of New Ross, but it’s still chilly when the wind bites; a feeble attempt at early spring. It’s Good Friday, and I’m standing outside St. Mary’s, an imposing defunct Catholic school in rural County Wexford, Ireland. Crew members scamper towards their lights and cranes. Two rows of haggard schoolgirls, heads lolling, are led by a nun through the yard. Incongruously, through the sunshine, a snow machine periodically emits suds that melt on your face as you pass: this is Christmas 1984 via Easter weekend 2023. There, amid a clutch of equipment and crew members in the usual onset menagerie, stands Cillian Murphy, producer and star of Small Things Like These, in a cinematic return to his native Ireland.

Murphy isn’t easy to spot straight away. Your eyes don’t immediately land on him as if following an unholy halo of superstar light; he is not presiding over anything or taking up extra room anywhere. That may seem strange, given that many of us have spent years watching his charisma on screen cut swathes through every scene, or gazing into those otherworldly ice-blue eyes that occasionally offer a flash of gangster malevolence.

A highlight reel of Murphy’s work is itself prodigious: there are his early days on stage in 90s London in friend and writer Enda Walsh’s play-then-film Disco Pigs. His speechifying leftist fervour in Ken Loach’s The Wind That Shakes the Barley. You might recall his transgender glam-rock singer in Breakfast on Pluto — but you almost certainly know his cold, feline grace in Peaky Blinders. And, of course, there was his sinister Scarecrow in Christopher Nolan’s Batman. Now his bespectacled visage can be seen in the promotional materials for this summer’s enormous new Nolan film: Oppenheimer. There, Murphy is playing one of the most recognisable historical minds of the 20th century.

Suffice it to say that the Cork native, 46, has one of the most distinctive faces — and careers — in contemporary film and television. “I remember very clearly, I saw a picture of him in the newspaper,” Nolan tells me over the phone from Los Angeles. “It was for 28 Days Later. He had his head shaved, and those extraordinary eyes. I hadn’t seen the film. It was just the look of him, it struck me.” Yet in person, that striking screen presence melts into total ordinariness: he is physically slight, unassuming, almost diffident. He sticks out his hand and introduces himself by his first name, like I was going to confuse him with anyone else.

Murphy is currently in between shooting exterior scenes, so he’s wearing the costume of his character, Bill Furlong, an 80s coal man with too many mouths to feed. That means a worn-in wax jacket, threadbare work trousers, artificially coal-dusted hands and a genuinely bleeding cut seeping across his knuckles (he caught it while shovelling in a scene). We sit side by side and drink coffee before he rushes off to shoot again, lifting breezeblocks from a lorry bed in the pretend snow of an Irish winter.

Small Things Like These, adapted for the screen from Claire Keegan’s acclaimed and heart-wrenching novella, was handpicked by Murphy: it’s his passion project. It’s become his first feature production credit on the strength of it being “an important story for Ireland”, he says. It deals with the insidious moral complicity of Irish society in the Magdalene Laundries. “Everyone in Ireland that you talk to, of a certain generation, more or less has a story. It’s just in Irish people,” says Murphy. “What happened with the church, I think we’re still kind of processing it. And art can be a balm for that, it can help with that.”

The production is set in New Ross following on from the book, and here at St. Mary’s, which actually operated as a laundry in the past, Murphy points out with an almost visible shudder that there are “ghosts”. I don’t think he’s being literal, but he goes on to say, “Being on location does something to the subconscious of the actors. I was very insistent that we didn’t build any sets, there’s no studio work: it’s all location work,” he says. “You can feel the texture, and in the tiny house where we shot you can feel the claustrophobia. The pressure comes in a real way. Chris [Nolan] is also a big fan of that. If you’re put in the right environment, you will act differently than to when you walk onset with your fucking soy latte or whatever.”

Murphy’s exacting attitude about his own project doesn’t seem far removed from the influence of Nolan, his long-time collaborator. They first worked together back in 2005, when Murphy auditioned for what would become Christian Bale’s role as Bruce Wayne himself before being cast instead as Dr. Jonathan Crane — Scarecrow — in Batman Begins. Thus began a collaboration that would lead to him playing J Robert Oppenheimer in one of this summer’s most highly anticipated films. “I was a Chris Nolan fan. That’s how I was when I met him for the first time, because I’d watched Following, I’d watched Memento, I’d watched Insomnia. And I met him for Batman Begins, and I met him on the basis of being a fan. So, it feels absurd that I’ve been in six of his films.”

It seems notable that at the height of his Peaky fame, Murphy took time to appear in Dunkirk in a cameo as a ‘shivering soldier’ with combat shock, a rather unshowy and minor role for an actor of his calibre. As Murphy points out, “I’d always show up for Chris, even if it was walking in the background of his next movie holding a surfboard. Though… not sure what kind of Chris Nolan movie that would be,” he laughs. “But I always hoped I could play a lead in a Chris Nolan movie. What actor wouldn’t want to do that?”

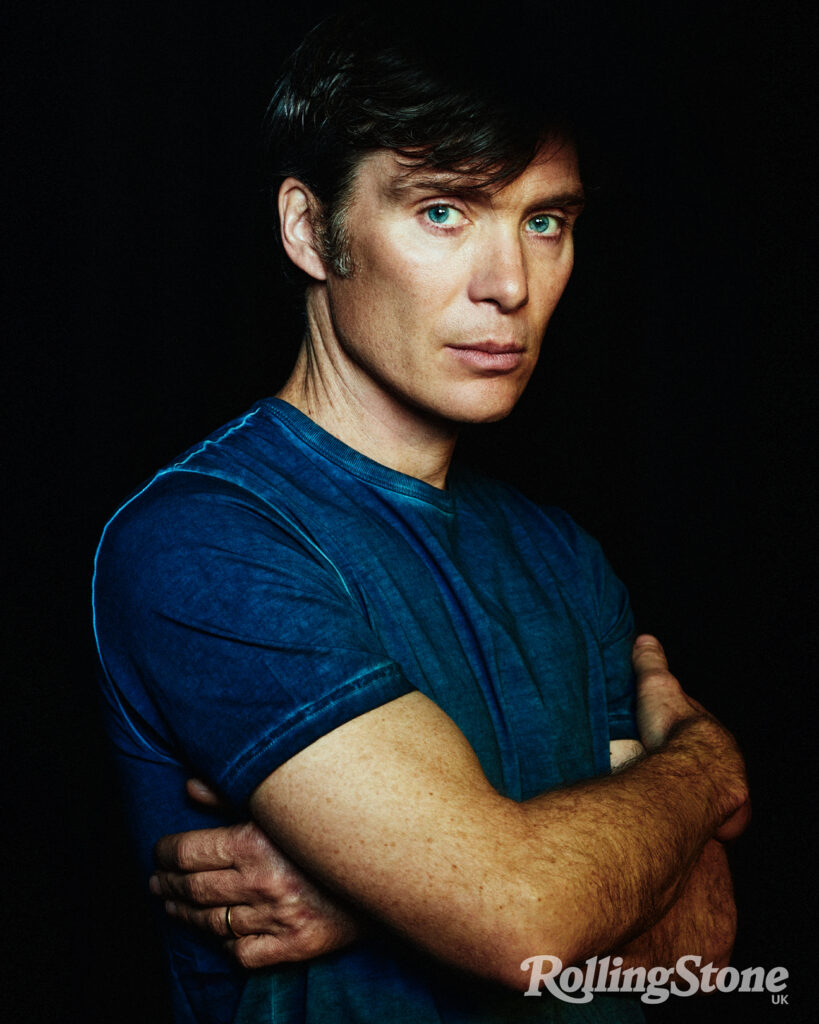

‘You start talking about acting and it’s like… when you shine a light on it, it disappears,” Murphy tells me the following day, as we sit in the empty top floor of a swish French restaurant in Dublin Bay. He’s looking a bit cleaner than Bill Furlong the coal man today, having just nipped over from his Rolling Stone UK cover shoot across the city. Without yesterday’s grime, he looks boyish, almost elfin. “Joanne Woodward said acting is like sex: you should do it and not talk about it,” he says. “And that’s why on set, with a good director, you rarely talk about the actual work. You talk around it, what you’re going to do next. I can do an immense amount of preparation, but then a lot of the action happens to you in real time. So, there is no value, really, in intellectualising anything.”

Murphy has a quicksilver intellect nonetheless, and we hop from masculinity to 70s Dustin Hoffman films to religion with ease. “My family wasn’t particularly religious, but I was taught by a religious order. The Irish school system was almost exclusively controlled by the Catholic Church, and still is to a large degree. And I went to church and got, you know, communion, confirmation and all of that. I have no problem with people having faith,” he says. “But I don’t like it being imposed. When it’s imposed, it causes harm. That’s where I have an issue. So, I don’t want to go around bashing the good things about institutionalised religion, because there are some. But when it gets twisted and fucked-up, like it did in our country, and imposed on a nation, that’s an issue.”

Given the subjects of his latest projects, which both, in their fashion, tell stories about institutional arrogance and the men who find themselves pitted against it, I ask him about learning lessons from cinema. “Maybe you get people talking when they leave the cinema. I love those films — provocative and political, but with a small p,” he tells me. “If you’re dogmatic and prescriptive, no one wants to watch it, but if it’s in an entertaining, stimulating film, people can watch it on two different levels.”

If it were to be said that Murphy specialises in anything, it might be physically expressing that multi-layered approach: the thoughts and motivations of inward men, who are not prone to garrulousness or fervent displays of emotion. Nolan certainly seems to think so: “Cillian has this extraordinary empathetic ability to carry an audience into a thought process. He projects an intelligence that allows the audience to feel that they understand the character and see layers of meaning.”

Such is the case with his decade-long characterisation of Tommy Shelby, the battle-scarred First World War veteran turned post-war criminal kingpin. So, too, with the very different character he plays in Small Things Like These, a monosyllabic working man who is nevertheless constantly lost in a web of thought and memory. From the limited materials so far released to the public in anticipation for Oppenheimer, Murphy’s turn as the father of the atomic bomb seems to be an equally interior role. The scientist became a symbol for our collective ambivalence about the bomb and the American deployment of it in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, but as a man, he was artistic and sensitive, a lover of poetry as much as of science, and a strident anti-fascist.

“I think Oppenheimer, of all the characters that I’ve seen Cillian take on and of all the characters that I’ve dealt with in my work, is one of the most complicated and layered people,” says Nolan. “Cillian is one of the few talents able to explore those different layers, and to project that level of complexity in a way that allows you to understand the character.”

Murphy is enthused at the opportunity to bring the story to the screen. “I think it’s the best script I ever read,” he says. The script was, per Nolan, given to the actor written entirely in the first person: the unusual move was immediately queried by Murphy. “He wanted it to be solely from Oppenheimer’s perspective. And I think the film is sensational. As a person who loves films — I’m not saying it ’cos I’m in the fucking thing, I hate looking at myself — but as a lover of film, as a cinephile, I’m a Chris Nolan fan.”

“Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” go the apocryphal words of the scientist upon witnessing his creation detonate for the first time at the Trinity test. We had entered the nuclear age, a threshold we can never conceivably uncross, our capacity for self-annihilation so elegantly and wickedly expressed by Oppenheimer himself. This was a man whose talent, idealism and hubris would lead him to ruin and dubious achievement: in other words, a dream for an actor like Murphy. “His ability to project power applies in a completely different way to a character like Oppenheimer, because Oppenheimer is this extraordinary strategic brain,” says Nolan. “There are all these levels of intention that are going on with the actions he’s taking, and he’s surrounded by people. So, the audience becomes members of this community who are hanging on to his every word, studying his every gesture, to try and understand it.”

Understandably, portraying such an elaborately brilliant mind had its challenges. “In Sunshine [Danny Boyle’s 2007 sci-fi movie], I played a physicist. I spent some time with [the physicist] Brian Cox, and he was a brilliant teacher,” Murphy says. “I’m never going to have the intellectual capability — not many of us do — but I loved listening. I enjoyed being around these insanely intelligent men and women and going for dinner to talk about normal shit,” he says. He offers some hints to his characterisation of Oppenheimer as he muses: “With that intellect — which I think can actually be a burden — you’re not seeing stuff in the normal plane that we do. Everything is multifaceted and about to collapse. It’d be a terrible way to buy milk or cut the grass, I’d say.”

Dislocation from the ordinary is hardly unfamiliar for Murphy. Congenitally private, he left London for Dublin about eight years ago with his wife, artist Yvonne McGuinness, and his two teenage sons. “We had 14 years in London. But I feel like as you hit your late 30s and have kids, living in a major metropolis is less exciting. And then also, you know, we’re both Irish. We wanted the kids to be Irish. I think it’s the best decision we made,” he says, pointing out that he sold his kids on it — now nearly 16 and nearly 18 — with the promise of the Labrador they now own.

“They’re really good boys. We have a laugh,” he says, affectionately. “We don’t do ‘Dad’s Movie Night’, but they like some of my films. They say all my films are really intense.”

Amid the increasingly frenzied obsession with Peaky Blinders, Stephen Knight’s series turned global phenomenon about 20s Birmingham gangsters, Murphy has become something more than an actor with a recognisable face: he’s become a cultural icon synonymous with Tommy Shelby, just as James Gandolfini did with Tony Soprano. It’s an uneasy negotiation for Murphy, who is strident about maintaining his separation from the noise. “It can ruin experiences, because it fetishises everything: you can be walking down the street and someone takes a picture like this is a fucking event. It kind of destroys nuance and human behaviour, but that’s part and parcel of it,” he says of his reluctant relationship with fame.

“Fame evaporates with regularity,” Murphy ponders, gesturing around the restaurant (a favourite haunt). “I’m around here all the time and no one gives a fucking shit. Nobody cares. I go to the shop. It dissipates. But if… one of the guys from Succession walked in here, I’d be all intimidated and shaky. When you’re confronted with someone you’ve invested a lot in, or you think is amazing, the encounter is strange,” he says.

There’s no sense of affectation about Murphy: he really does dislike all of the rigmarole that comes with promoting a project. When I leave him in New Ross the night before our interview, he says to me: “I look forward to my grilling.”

“A light grilling,” I reply, a bit taken aback by what seem to be genuinely jangling nerves on his part.

Later, he sighs while relating how, “Fame is like commuting. You have to commute to get to your destination.” Don’t get him wrong, he doesn’t like to complain, but it is the work, above all, that he values. “I think that’s the way the best people are: they’re not doing it for any other reason but love of the craft. They have a compulsion to make work, not to be famous or get attention,” he says, by way of praising Irish colleagues like Kerry Condon and Barry Keoghan.

“I don’t really partake. I don’t go out. I’m just at home mostly, or with my friends, unless I have a film to promote. I don’t like being photographed by people. I find that offensive. If I was a woman, and it was a man photographing me…” he trails off. Attempting some levity, I point out there are worse things than women fancying him. “No comment,” Murphy replies firmly. “I think it’s the Tommy Shelby thing. People expect this mysterious, swaggering… it’s just a character. I do feel people are a little bit underwhelmed. That’s fine, it means I’m doing my job. Peaky fans are amazing. But sometimes I feel a little sad that I can’t provide — like — that charisma and swagger. He couldn’t be further from me.”

After the season 6 finale aired last summer to hosannas from fans, talk was ignited around a possible Peaky Blinders film, with Stephen Knight confirming the plans. Murphy is currently working with the team on putting the movie together. “If there’s more story there, I’d love to do it,” he says. “But it has to be right. Steve Knight wrote 36 hours of television, and we left on such a high. I’m really proud of that last series. So, it would have to feel legitimate and justified to do more,” he says.

As the evening winds down, Murphy seems visibly more relaxed. He’s clearly happier talking about Inside Llewyn Davis and Joni Mitchell than himself. Given his interest in music — he tells me that his record collection is his greatest extravagance, and how his teenage band was nearly signed to a major label — I wonder if he’d be game to introduce a musical component into his film work.

“I almost want to protect my relationship with it,” he says, reflecting on his love of music. “It was my first love, and I worked really hard at trying to be a musician and it didn’t work out,” he says, tugging on the sleeves of his jumper. “But I’ve turned down quite a few biopic roles of musicians,” he reveals, although he won’t say who. “I’d much prefer to watch a three-hour Scorsese doc about George Harrison than play George Harrison in a bad wig,” he says. There’s a beat. He smiles. “It wasn’t George Harrison I was asked to play, by the way.

“I will never release any music of my own, never, ever,” he continues. “I want to do one thing well. And I guess because I’m still a little sore about being a failed musician.”

Music is still nipping at Murphy’s heels: he admits his go-to when feeling low is The Beatles Anthology, along with Peter Jackson’s 2021 series Get Back. When he puts on his driving playlist during the photoshoot, 70s krautrock blares out (Can’s ‘Vitamin C’, natch.) Later, catching a snap of himself looking unusually jovial in a full-length black leather YSL trench, (photographers never usually ask him to smile, he points out), he says: “I look like Lou Reed just told me I was cool.”

When he’s relaxed, there’s a low-key humour to Murphy, and he swears constantly, a refreshing punctuation for most of his sentences given his often-serious demeanour. It makes for a curious combination: self-deprecating, workaday Irishness (“Don’t be silly,” he immediately says at the idea he might be intimidating, momentarily forgetting that he has played a Batman villain), and also something granite-hewn. (“Be calm and controlled in your life and furious and chaotic in your work. Or something like that,” he says, paraphrasing Flaubert.)

“No” is a full sentence with Murphy, as I soon learn. It’s the same in his creative projects, according to people who’ve known him for years: he’s unstoppable in pursuit of what he wants, and equally stone-stubborn if he decides against something. “He’s always looked to challenge himself. He’s never been an actor to rest on his laurels,” says Nolan of his leading man. “He’s the same guy he was. He hasn’t let success change him or get in the way of the truth of this process in any way. And that’s a very difficult thing for an actor to maintain across a career.”

Murphy’s intractability is also his integrity: it’s probably how he has maintained one of the most respected and variable careers in the business, never seeming to settle for the voguish or vanilla. But he’s typically prosaic about it. “I’m totally fragile and insecure, like most actors,” he tells me. “It’s putting your head over the emotional parapet. It’s fuckin’ hard. It’s a vulnerable place to be.”

Back in New Ross, the sun has set and production is ongoing; a few of us have retreated into a tent with a monitor and a headset through which we can see and hear the shooting — and the conversations between Murphy, director Tim Mielants, and co-star Zara Devlin. Technically, this is a simple scene: his character has to enter a coal shed and discover a fragile, freezing teenage girl, put his arms around her, and guide her out. It begins that way, simply a geometry lesson of angles, light and movement. Through the headset, I listen as Murphy suggests re-blocking the scene; chewing ice cubes to make the actors’ wintery breath appear; changing the way he enters the frame. Every idea helps. It’s a marvel of collaborative filmmaking, brick-by-brick emotional and visual construction as each take noticeably improves. Long-time producer Alan Moloney murmurs with tacit approval that “Cillian interrogates everything.”

But it’s when Murphy and Devlin begin to improvise, murmuring to one another in low voices, that an electric energy seems to charge through the set. A simple scene becomes a heart-breaking one; a gruff, terse man shows a brief glimpse of soft underbelly, an understated emotional vulnerability all the more powerful for its restraint.

When the filming breaks, Moloney exclaims joyfully. Murphy stands in the car park with his hands in his pockets; suddenly he looks delicate. He’s back behind the parapet, where it’s safe for a moment. But it’s pretty clear he’s good and ready for the skirmish.